Linguistic signs are mostly arbitrary in the sense that their

form is not directly related to the concept they express. For example, there is

nothing in the phonetic shape of the Malay word ikan to suggest its meaning – ‘fish’,

or, by extension, any ‘marine animal’ (turtle, whale, oyster, etc.). The sound

of the word is not intended to evoke swimming or splashing. It is just a

regular historical reflex of Proto-Austronesian *Sikan (with the same meaning

and also an arbitrary phonetic shape). It has cognates in other Austronesian languages, for example Hawaiian i‘a [ˈiʔa].

None of them makes you say to yourself, “Methinks it is like a fish.” Indeed,

even if a word starts out as onomatopoeic, sound changes will in the long run alter its pronunciation beyond recognition, eventually reducing or destroying its imitative value (see the etymology of English pigeon).

Affixes and auxiliary words are usually not iconic either. English regularly indicates the

plural number of nouns with the suffix -(e)s (pronounced [s, z, ᵻz], depending on the context); some nouns (including fish) form endingless

plurals. Neither the suffix nor its absence “portrays” plurality, whether by

resemblance or by analogy. The same can be said of irregular plurals like goose : geese or child : children. Is it possible at all to express plurality iconically – that is, to make a linguistic sign

sound plural? Yes, it can be achieved by amplifying the

sign itself to indicate “more of something”; and one simple way to amplify it is to repeat it. Malay nouns are not inflected for number.

Plurality, if it matters in a given situation, may be signalled by the use of

numerals or quantifiers, or just inferred from the context. But the speaker may

also choose to emphasise the multiplicity of referents by doubling the noun:

ikan-ikan ‘fish’ (plural). This is similar to emphatic repetition occasionally

encountered in all languages, including English, as in:

We rode for miles and miles.

What do you read, my lord? ― Words, words, words.

In English,

word repetition is a syntactic phenomenon; in Malay, it is used as a word-formation mechanism. Note, by the way, that many Malay nouns obligatorily consist of a double occurrence

of the same sequence and have no simplex counterpart, e.g. biri-biri ‘sheep’ (singular and plural), while others change

their meaning if doubled (mata ‘eye’ : mata-mata ‘spy, detective, police

officer’). Root-doubling can also be used with adjectives to indicate intensity

(her wild, wild eyes could serve as an English analogue), and with verbs to indicate repetitive or

prolonged action. In those cases the doubling is definitely iconic. But duplicated

verbs may also refer to a sloppy or leisurely execution of an action, e.g.

makan ‘eat’ : makan-makan ‘peck at the food’ (showing lack of interest or appetite). Here the iconicity is less self-evident.

The technical

term for such morphological doubling is reduplication. In the Malay examples above

the entire root is faithfully repeated, but numerous languages also employ

partial reduplication in which the repetition is just hinted at rather than

applied in full. Typically, a fixed pattern of consonants (C) and vowels (V) is

used as a simplified copy of the morphological base – most often a CV or CVC template.

Sometimes only the consonants are copied from the base, while the V position is

filled by a fixed default vowel (e.g. [ə]). Depending

on the language, the copy may be attached before the base (as a prefix) or after it

(as a suffix), or even inserted inside it (as an infix). The copy is usually called reduplicant,

but I prefer the handier and less esoteric term echo. We shall be mostly concerned

with reduplicative prefixes, that is cases when the echo is placed before the base. For example, in Yucatec Maya

CV reduplication is employed to form intensive adjectives and intensive or iterative

verbs:

k’aas ‘bad’ : k’a’-k’aas ‘evil’

p’iik ‘break (something hard)’ : p’i’-p’iik ‘break into many fragments’

Partial reduplication of this kind is not unlike stammering, which may also involve incomplete syllable repetition: b—b—black [bəbəˈblæk]. Of course there is an important difference: reduplication is controlled by the speaker, while stammering is involuntary and has no grammatical function.

Expressing

plurality, intensity, repetition or, more generally, “greater degree” is the

most natural use of reduplication, with a clear cognitive motivation. However,

once adopted as a derivational or inflectional device, reduplication easily acquires

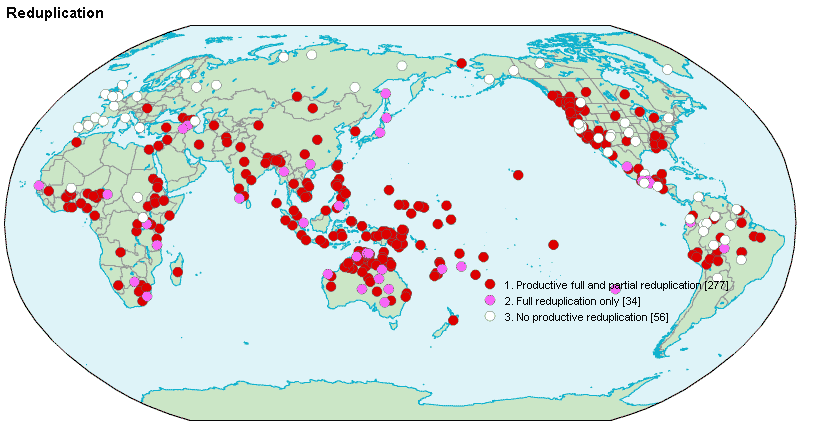

secondary functions, gradually dropping its iconic character and evolving into another “arbitrary” morphological tool. Reduplication, in its numerous variants, has a global distribution. It’s only in a circumpolar belt of the northern hemisphere, including Europe, Northern Asia and the

northernmost part of North America that reduplication

plays little role in derivational and inflectional morphology. From a

Eurocentric perspective grammatical reduplication may look exotic; we shall

see, however, that it had important functions in Proto-Indo-European and some of the languages

descended from it.

See also: WALS Online: Reduplication

I hope we hear about Class VII strong verbs soon. English does have a lot of expressive morphological reduplication: ragtag, peepee, chitchat, and fancy-shmancy, to pick four words from four different types. And of course the technical term redup-reduplication

ReplyDeleteProbably all languages have expressive and onomatopoeic reduplication (or rhyme-reduplication). One could also add reduplicative dvandva compounds like fifty-fifty. When linguists say that reduplication has little importance in the languages of Europe, they really mean that its use is limited to such types.

DeleteEve Merriam, "By the Shores of Pago Pago"

DeleteIn my opinion, all words would ultimately derive from onomatopoeias, but at a time depth exceedingly old, dating back to the origins of language.

DeleteOops! I almost forgot, but Latin faber 'smith' ultimately derives from an onomatopoeic lexeme (I prefer not to use "root") *tap- ~ *dab- alluding to the hitting of metal. But the clumsy Pokorný (I think this is the right spelling) made a mess of it in his dictionary.

DeleteWell, if you think all words are ultimately onomatopoeic, then it stands to reason that faber must be ultimately onomatopoeic too. There's no need to repeat the same opinion about each and every word separately. ;)

DeleteOh! But in this particular case the chronology would be much more recent, post-Neolithic, because faber is related to metallurgy.

DeletePokorný (I think this is the right spelling)

DeleteThat's the etymological spelling; apparently, the good man didn't use it himself, having grown up in German-speaking places.

In the phonebook of Vienna you'll find Czech and Slovak diacritics used or not used pretty much at random.

"an onomatopoeic lexeme (I prefer not to use "root") *tap- ~ *dab-..."

ReplyDeleteWouldn't *dab contravene a root structure constraint?

Oh! In standard reconstructions it appears as *dhabh-.

Delete