The final /θ/

of filth no longer plays any useful morphological function. It has become fused

with its derivational base into an indivisible whole. This is quite often the terminal

stage in the life-cycles of linguistic replicators. Old English -þ- was still a morpheme, but it

had already lost most of its phonological substance. A few hundred years earlier,

in Proto-Germanic, its ancestral form had been *-iþō, continuing still earlier (pre-Germanic)

*-étā. A linguistic entity that used to be a suffix of some length has ended up

as phonological raw material. It means nothing by itself and has degenerated

into a speech sound which, together with three others, encodes a meaning (or

rather a cluster of meanings) but is no different, as far as its status is

concerned, from the final /m/ of film.

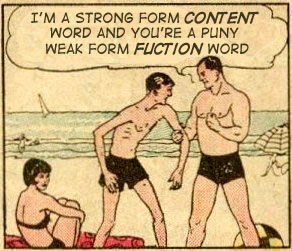

Whole words

may become reduced to the role of ‘bound’ (non-independent) morphological

elements. Many derivational affixes used to be words which, through being

frequently used in composition, survived in that function while their

free-standing variant went extinct. Old English hād meant ‘person, social

status’. When added to a noun it meant ‘the state or condition of being an X’.

Hence, for example, OE ċild-hād ‘infancy, childhood’. The word hād > hǭd lingered

on in Middle English, but seems to have become rare by the thirteenth century and

eventually died out as an independent word. Curiously, in modern ‘gangsta’

slang hood (no connection with hood = ‘head covering’) is used as an abbreviation of neighbourhood. It has become a word

again, though with a brand new

meaning.

|

| Words have fractal-like properties: the more closely you look at them, the more structure they reveal |

When such

reduction and fusion processes have operated for millennia, they may compact a whole

string of morphemes into a short word without any visible internal structure.

If you look at young /jʌŋ/ today, it’s short even for an English word. In the

reconstructed remote ancestor of English, the Proto-Indo-European language, it

looked roughly like this: *h₂ju-h₃n̥-ḱó-s. The first

element, *h₂ju-, was the compositional variant of the noun *h₂óju

‘vitality, youthful vigour’; the second was a suffix (possibly derived from an

independent word) meaning ‘having, loaded with’. Together they formed the noun

*h₂jú-h₃on- meaning ‘energetic young man’ (literally: ‘having

the strength of young age’, cf. Skt. yúvan-). The addition of the suffix *-ḱó-

produced an adjective with the meaning ‘like a young man, juvenile’. We find

its reflexes for example in Sanskrit (yuvaśá-), Latin (iuvencus), Welsh (ieuanc

~ ifanc), and of course in the Germanic languages (PGmc. *jungaz > OE ġeong ~ iung [juŋg] > young). In other words, the /jʌ/ part of young is what has remained

of a once independent noun, and the /ŋ/ represents two concatenated morphemes

compressed into a single segment. Incidentally, *h₂óju is a very

interesting item in the Proto-Indo-European lexicon, and I hope to return to it

soon.